Introduction

The MKH 418-S stereo shotgun mic was introduced in 2003, creating – by addition of a fig 8 capsule – what was essentially a mid-side (MS) version of the popular mono MKH 416 shotgun mic. The new MKH 8018 does something similar for the MKH 8000 family of mics, although its mid mic is less directional than the MKH 8060 short shotgun and, of course, a lot less so than the longer MKH 8070. While the specs are significantly improved on the MKH 418-S, the MKH 8018 is aimed squarely at a similar market – most obviously outside sports broadcast. A few reviews have begun to appear on the mic and, rather than repeat ground covered in them, the focus on the tests for this blog post is a bit different: as usual I explore the basics (self-noise, handling noise, frequency response, resistance to RFI etc.), but the field tests focus on the performance of the MKH 8018 as a stereo mic. Above all, I am interested in how this latest take on a stereo shotgun compares to a non-shotgun mid-side pair and, for this, it seems most appropriate to test it in parallel to an MS pair of its MKH 8050 (supercardioid) and MKH 8030 (fig 8) siblings. How can the useful side rejection of a mono shotgun be reconciled with the addition of a fig 8 to create a stereo signal? Likewise, the tight focus of a shotgun mic for some sound effects can be useful, but how does a stereo version work for this? Does the inevitably more erratic (lobar) polar pattern of the shotgun mic at higher frequencies render it very much a poor cousin, or is it eminently usable? Is this mic about having that tight mono shotgun perspective, but with instant flexibility (without changing rig, or, even, making the call in the field) to have that stereo image when useful? If any of these or related questions are of interest to you too, then read on!

PS I should add that the good folks at Sennheiser sent me this MKH 8018 gratis for my unfiltered scrutiny. As usual, I play a straight bat and do my best to be objective (and, if anything, my starting point is a little scepticism about MS and, consequently, DMS with shotguns, as readers may have noticed!), and, with plenty of test WAV files to download, you can pore over my tests and draw your own conclusions. Right: onwards!

PPS It’s not the shortest blog post ever, so if you are after sound samples, stick with it: mostly they are further down.

A look at the mic and its specifications

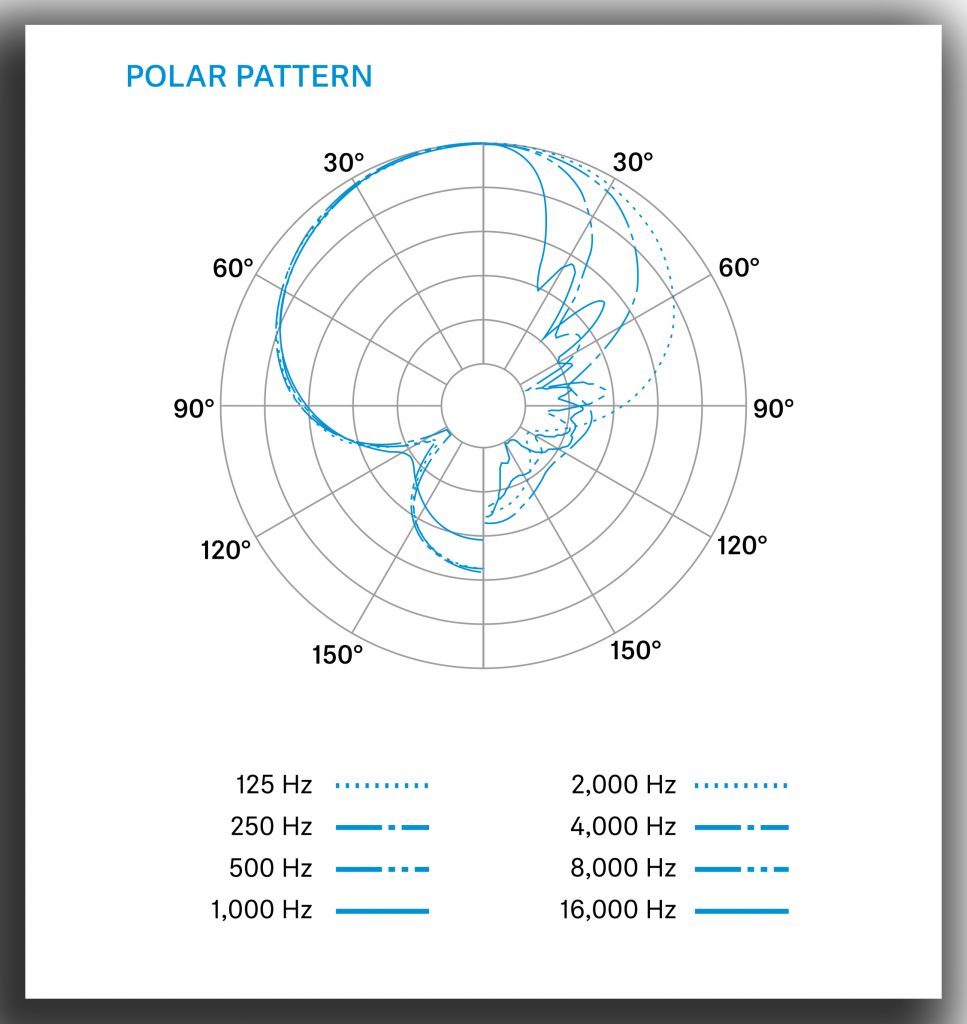

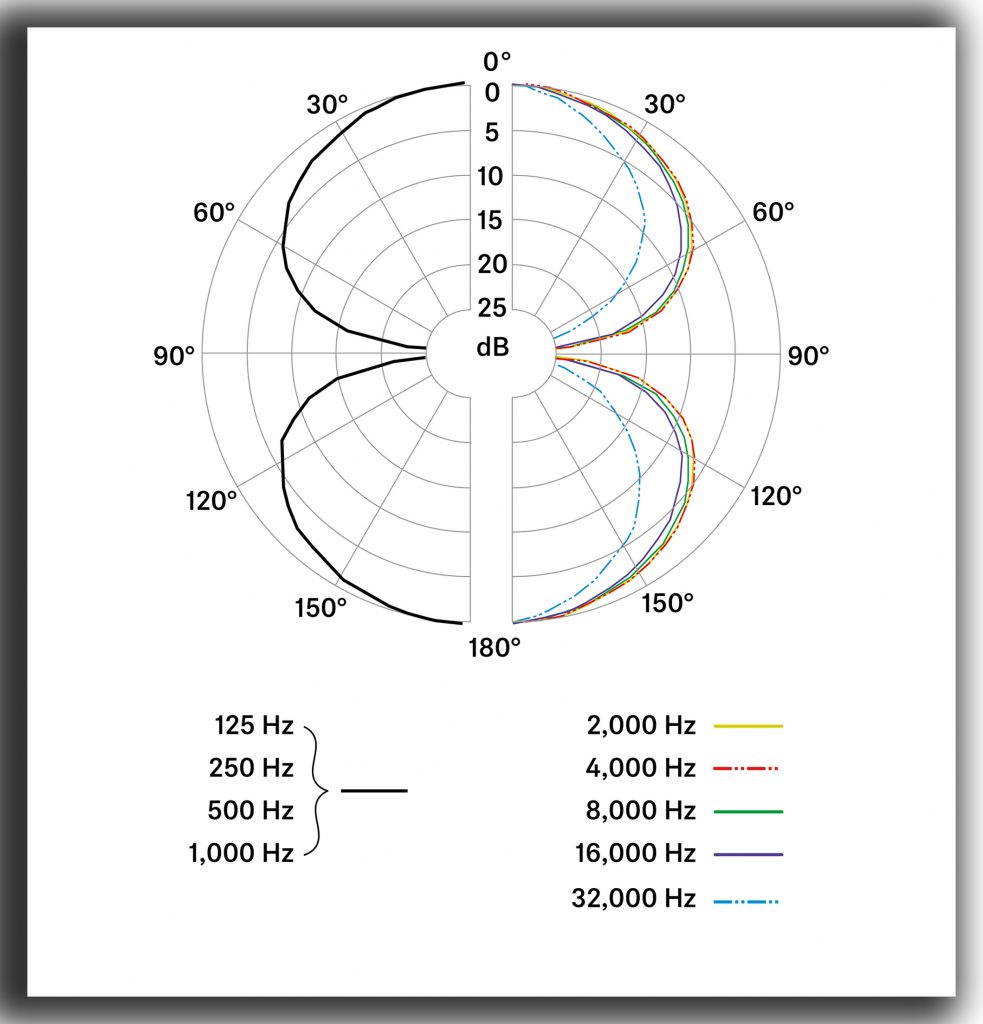

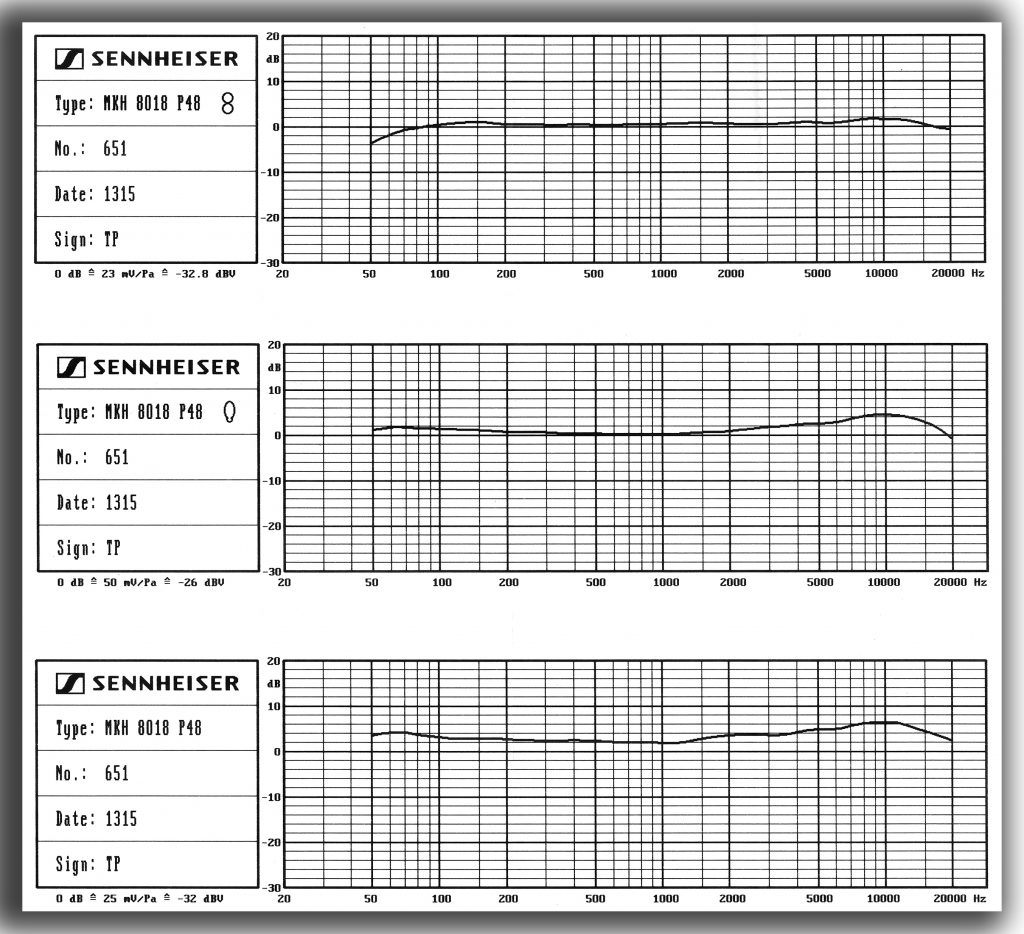

Well, first to the mic itself. There is no great value in repeating the specifications provided on the Sennheiser website, but a few key ones jump out and merit some discussion. First, of course, is the self-noise, for which figures of 12 dBA are given for the mid (shotgun) mic capsule and 14.5 dBA for the side (fig 8) capsule. These are lower than for the MKH 418-S, for which the mid channel is 14 dBA and the side channel 22 dBA. The fig 8 self-noise improvement is very substantial, but, interestingly, the value is not the same as that for the recently introduced MKH 8030 (13 dBA). The polar pattern of the MKH 8018’s fig 8 is also much less regular than that of the MKH 8030 above 4kHz, which, with the self-noise difference, suggests a different capsule, which Sennheiser have confirmed. The shotgun mic capsule appears to be different from the MKH 8060, and, again, I have had this confirmed…

The MKH 8018 is also a lot more sensitive than the MKH 418-S: for the mid (shotgun) capsule -25 dBV vs -32 dBV; and for the fig 8 capsule -32 dBV vs -40dBV. In both cases, in actual use the substantial difference between the sensitivity of the mid and side channels is then amplified by the fact that the side channel usually gets a much lower signal. In practice I have run 7dB more gain on the side channel in the field with the MKH 8018, to get the capsules up to matching sensitivity, but that’s not always easy with some mixer/recorders with MS linking. And while the MKH 8018 shotgun capsule has quite a hot output, it isn’t unusually so: for example, the MKH 8060 is 1 dBV hotter at -24 dBV.

Thinking about the sensititivies of the two channels leads to another key difference between the MKH 8018 and the MKH 418-S: while the latter outputs the M and S signals only, the MKH 8018 can switch between this option, ‘narrow-XY’ and ‘wide-XY’. No information is given as to the ratio of M to S in the two decoded LR stereo outputs and, while I am sure that they will prove useful to some not familiar or unable to work with the M and S outputs, for all my testing and use I have had the mic set in its MS output mode: I like to know what I am doing!

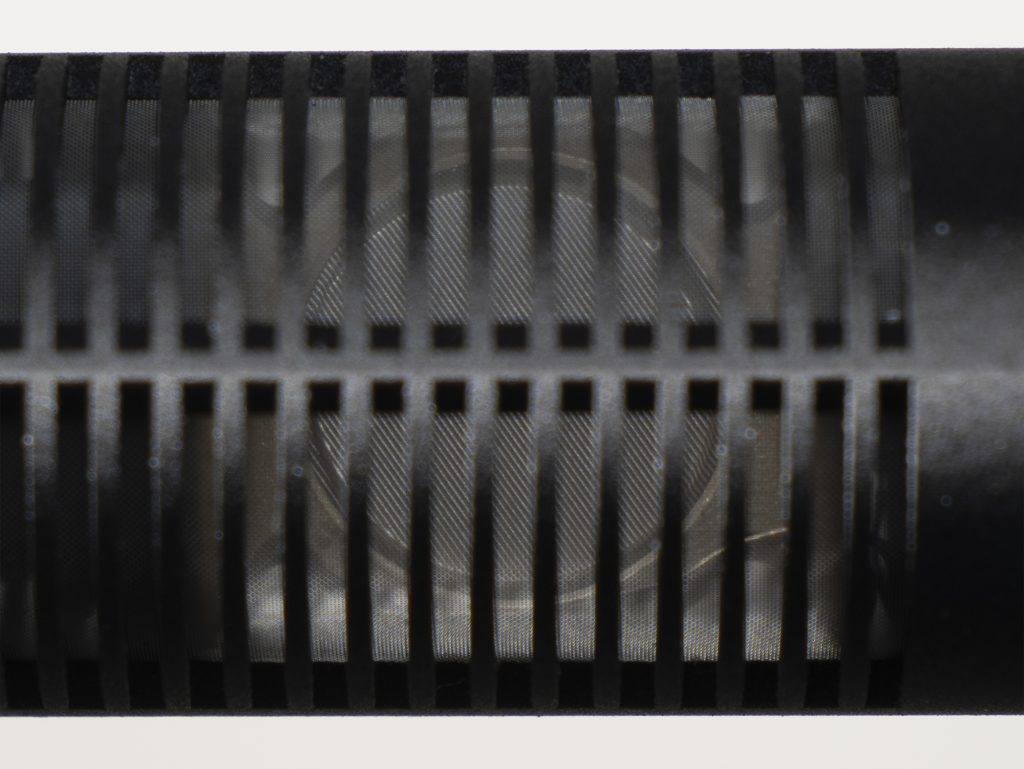

Turning to the physical appearance of the mic itself, all is exactly described and illustrated on the Sennheiser website. The one thing that wasn’t clear from that was the position of the capsules within the mic, so the first thing I did on opening the box was to hold the mic up to the light to try to see what is going on.

Capsules and polar patterns

Polar patterns vary much more across the broad category of shotgun mics than across the individual types of first-order mics (omni, cardioid, supercardioid, hypercardioid, fig 8 etc.). Shotgun mics also have a much more variable polar plot at different frequencies than mics with no interference tube. For example, a shotgun mic might have a similar acceptance angle (signal no more than 3dB down on the on-axis signal) as a hypercardioid (i.e. 105°) up until 1-2kHz, before narrowing (i.e. getting more directional) above that to, say, 25° at 16kHz. So the simple distance factor (i.e. the distance at which the mics get the same direct-to-diffuse field ratio) that can be described for omni mics through to fig 8s has no immediate application to shotgun mics: you will read of ‘typical’ distance factors for shotgun mics of 2 to 3 (with an omni being 1.00, a cardioid being 1.73 and a supercardioid being 1.90), but, clearly, this is a crude approximation given the change in directivity with frequency. Adding to the variables in design (inc. length) of the interference tube and capsule, multi-capsule shotguns also change how the mics reject off-axis sound. The polar pattern (with its particular frequency dependent variation), therefore, has a much more significant role in determining which model of shotgun mic a sound recordist will choose for any given type of recording situation. That doesn’t mean, of course, that the published polar patterns are what a recordist uses to make such choices: an experienced sound recordist will usually base that on how they have heard different microphones perform in use in a range of situations.

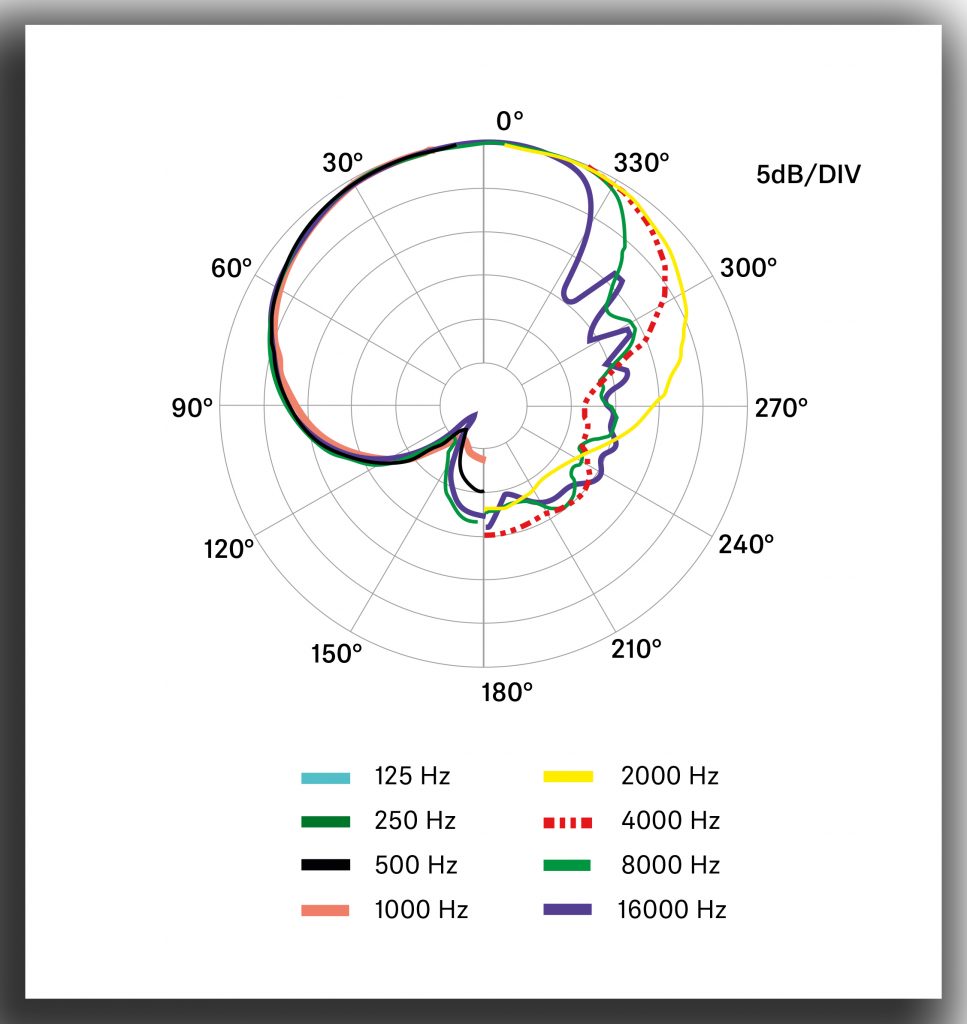

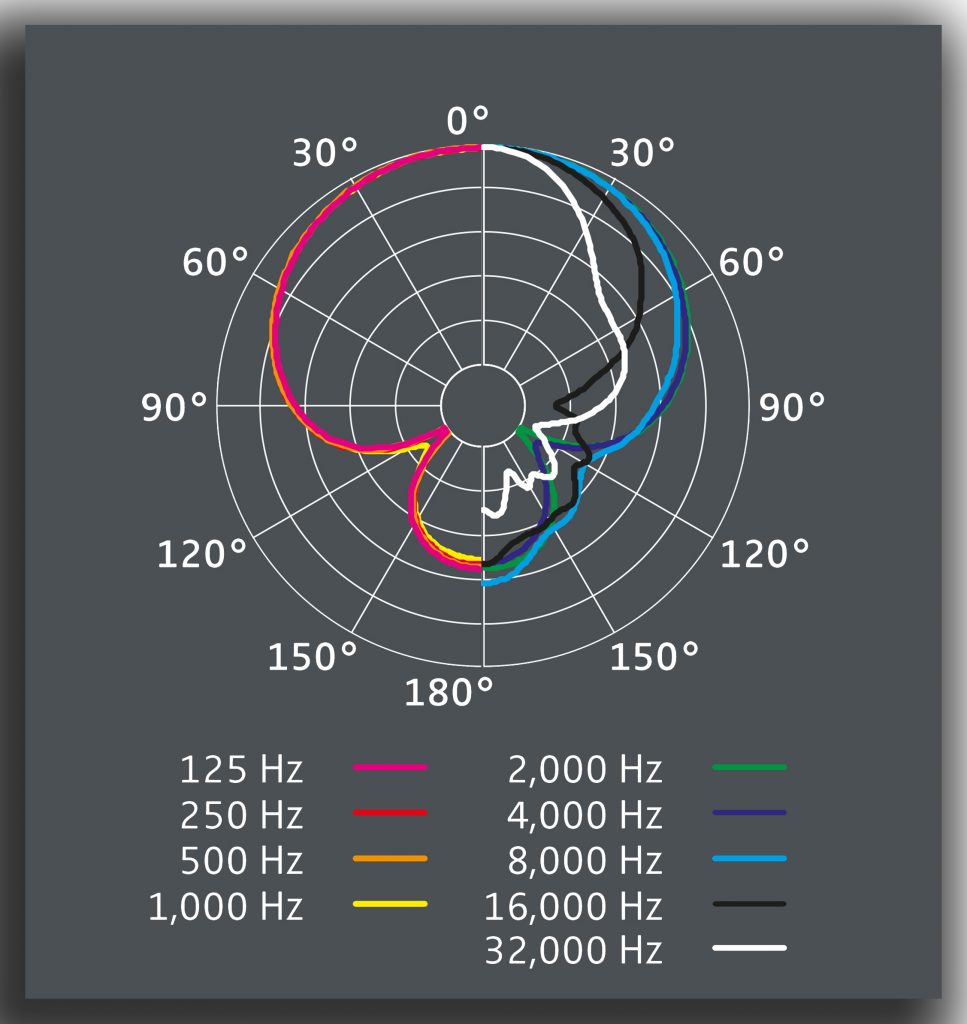

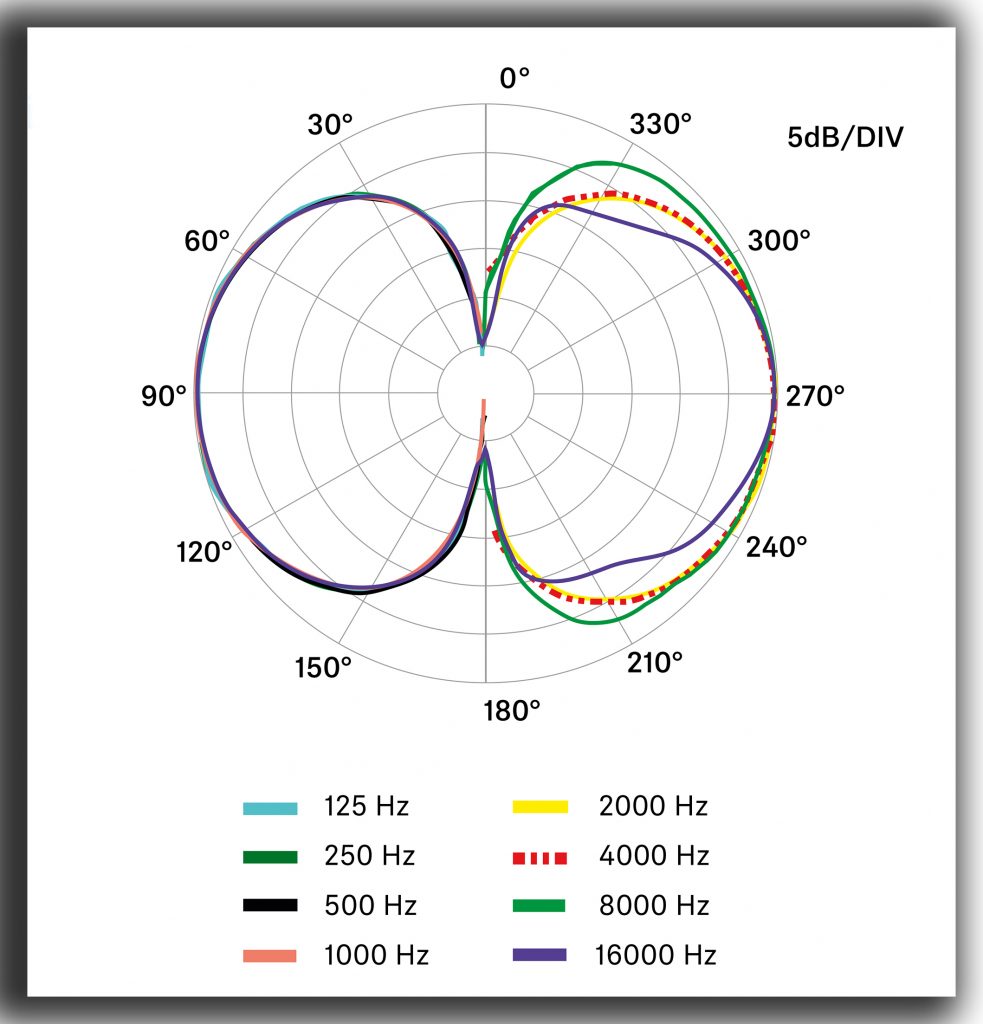

Nonetheless, a polar plot, especially if not overly smoothed, contains useful information for a shotgun mic, and it certainly gives an immediate insight into the MKH 8018. This shows that at lower frequencies, up to 1kHz, the MKH 8018 mid mic has a very slightly wider pattern than the MKH 8060, and, indeed, fractionally more so than the supercardioid MKH 8050, but with a much smaller rear lobe than either. Above that there is more divergence: by 2kHz the MKH 8060 has a significantly tighter pattern and this increases with frequency, along with a less noticeable rear lobe. The MKH 8018 and MKH 8050 remain very similar up to 4kHz, but, thereafter, the MKH 8018 gets more directional, as you would expect. As with all polar plots for interference tube mics, by 8kHz that for the MKH 8018 shows erratic, or lobar, form, but the response from a sine wave at a specific frequency is very hard to translate to use: this is where listening to the mic is critical. Hopefully the various test files in this blog post will help, but there’s no substitute to testing for yourself, especially when comparing to a mic known to you.

Turning to the fig 8 capsule, as I said in the introduction, its specs are similar but not identical to that of the new MKH 8030. I am loathe to take the new MKH 8018 apart, but, despite the fine mesh of the mic, careful lighting shows the position and appearance of the capsule. It is positioned (to the rear of the shotgun mid mic capsule, obviously) so that it is centred on the seventh slot from the end of the interference tube (so 12.5mm from the solid part of the mic body), and its appearance is very close to that of the MKH 8030, with a similar stainless-steel filter over the usual MKH symmetrical push-pull single diaphragm, and a brass tensioning ring around it that looks identical to that of the MKH 8030 apart from the mount detail, which, in this case, widens for the fixings at both ends (one end joining to the mid mic capsule). Unlike the MKH 418-S the fig 8 capsule (KS-16-3) does not sit in an oblong block, but, rather, has a rounded tension ring. It appears that, like the MKH 8030, the fig 8 in the MKH 8018 has a16mm-diameter diaphragm, but that is based on a visual estimate compared to the overall mic diameter (22mm). It is a little surprising, given the visual similarity of the MKH 8030 and MKH 8018 fig 8 capsules, that they don’t have identical specs, although in the case of the difference in polar patterns it is unclear whether this relates at all to, in the case of the MKH 8018, the mounting between the preamp and the mid mic capsule (given the nulls it is hard to imagine why this should be so), or indeed the less open slotted tube and close mesh that continues across the fig 8 part of the MKH 8018 vs the more open design and open weave mesh of the MKH 8030. Here are the comparative polar patterns:

The different presentation (90-degree rotation and split vs continuous circles) of the two polar patterns doesn’t disguise the fact that they are quite different, with significant irregularities from 2-4kHz upward in the MKH 8018.

Frequency response

Like the MKH 8060 and MKH 8070 shotgun mics the MKH 8018 also has a more limited frequency range than the rest of the MKH 8000 mics. The published figures for the latter are all 30 Hz to 50 kHz, apart from the omni MKH 8020, which has a published range of 10 Hz to 60 kHz. The frequency range given for the MKH 8018 is 40 Hz to 20 kHz, but looking at the plots above you can see that the fig 8 side mic is shown as having much less low end: fig 8 mics are often a little bass-shy compared to other polar patterns, although this shows a steeper fall-off than with the MKH 8030. As discussed in previous posts, an extended high-frequency response might seem entirely academic outside those recording at high sample rates and pitching down in post (e.g. for bat recordings, or for sound effects), but there are those that argue frequency response over 20kHz is important for high-resolution recording (such as David Blackmer of Earthworks mics in this article). But quoted figures of themselves do not tell the whole story (for example the extended high-frequency capabilities of the first-order MKH 8000 mics comes with a sharp rise in self-noise, which can be problematic for very quiet sounds), so for a field test, I again thought the overtones of some church bells would be an interesting sample, so up I clambered to the belfry at Norwich Cathedral.

For the recording I set up the MKH 8018 and an MKH 8050 + MKH 8030 MS pair in separate Mini-ALTO windshields (there was a breeze inside the belfry) facing the bell-frame. Such a loud sound really brings home the sensitivity of the mid (shotgun) capsule: 20 dB gain was pushing my luck! Here are the 96 kHz sound files:

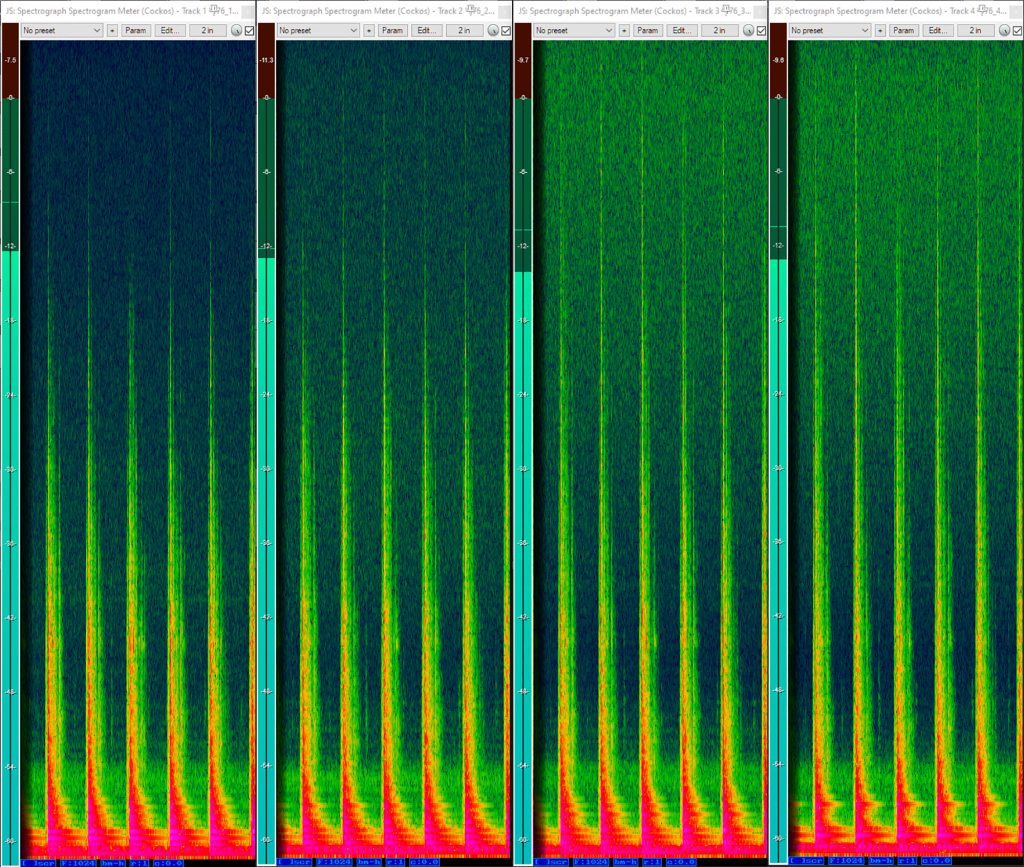

And here is a spectrogram of part of the recording, showing the chimes. The higher-frequency capability of the MKH 8030 and MKH 8050 are evident with much stronger signals up to 48kHz (the limit on this spectrogram), but, equally, so is the much greater self-noise of these mics from just below 20 kHz and upwards compared to the MKH 8018 (see below for more on self-noise). And while the latter might only be quoted as having a frequency-range up to 20 kHz, like many similarly specified mics there is no abrupt cut-off at this point and there is plenty of signal above this frequency.

Turning to the other end of the spectrum, I set up the MKH 8018 and the MKH 8050 + MKH 8030 pair aimed at the exhaust pipe of the rear of a parked car (with the engine running needless to say!). Here are short clips from the recording, which include a little gentle revving:

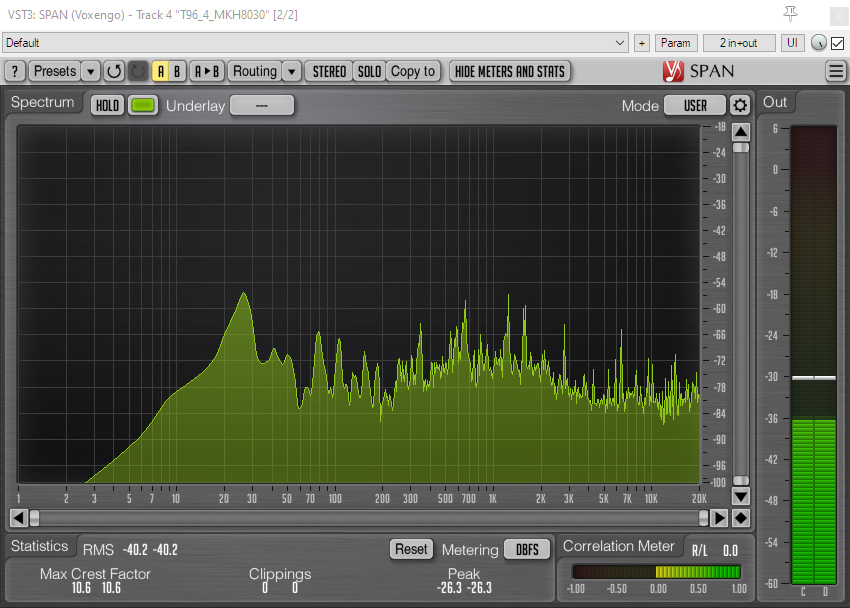

And here are the spectrum analyzer visualizations:

The tracks show all four capsules capable of rendering the lowest fundamental, which was around 26.5Hz, although, of course, the fig 8s show a lot less of the low-end of the engine: this is partly since the exhaust pipe itself was centred on their nulls and partly since fig 8s inherently have a poorer low-frequency response. What is more interesting is that, compared to their MKH 8050 + MKH 8030 counterparts, both MKH 8018 capsules have a greater low-frequency output down to around 50Hz, but a lower output at the 26.5Hz fundamental and then fall away quickly below that. It is comparable to using an MZF 8000 ii filter module on the modular MKH 8000 mics, with its permanent low-cut filter of –3 dB @ 16 Hz, 18 dB/oct: indeed, the comparison is especially valid (and I assume a design intention) since both the MZF 8000 ii filter module and the MKH 8018 have a switchable low-cut filter of -3 dB @ 70 Hz. So without use of the switchable low-cut filter, the MKH 8018 seems to have a steep roll-off of the very low frequencies likely to arise from handling noise (and the inevitable resonant frequency of a mic suspension); and then the option to roll-off more (often not optional in many shotgun mics) at a higher frequency to reduce wind noise, traffic rumble and, even, higher-frequency handling issues. In short, the design allows the MKH 8018 to be used where many a shotgun mic would struggle for lack of low-frequency response, yet is designed with handling in mind and has the option to roll off more low-end in keeping with many a shotgun mic: and the response of the two capsules is consistent in this regard.

Self-noise

The 12 dB-A self-noise figure for the MKH 8018 shotgun mic capsule is respectable for a shotgun mic and as we have seen it is an improvement on the mid mic in the MKH 418-S stereo shotgun (14 dB-A), and only a little higher than the figure for the MKH 8060 shotgun mic (11 db-A). And, while the side mic capsule of the MKH 8018 might have a little more self -noise than the MKH 8030 fig 8 (14.5 dB-A vs 13 dB-A) that is still very good for an SDC fig 8 and radically better than that in the MKH 418-S. But specs of self-noise are one thing and how they sound can be quite another: a single figure doesn’t tell the whole story. So on to some tests…

First off, I checked that the manufacturer’s sensitivity figures were broadly correct, recording a 1kHz tone and measuring that with a tight band-pass filter applied at 1kHz: all was evidently in order at least in relative terms (I compared the two MKH 8018 capsules to an MKH 8030 and an MKH 8050 [also 13dB-A], getting a maximum deviation of 0.8 dBV from the published specs). So, in the absence of an anechoic chamber, I then did my usual recording the sound of nothing with the mics buried deep in duvets in the airing cupboard, with all doors and windows closed and the mains electricity turned off, recording with each mic at 76dB gain (the max of a Sound Devices 788T). Also as usual, to remove any low-frequency sound still permeating, I applied a 100Hz high-pass filter, and, in my DAW, added further gain to match the three less sensitive capsules with the sensitivity of the MKH 8018’s mid mic (the hottest of the four capsules). Normally, I wouldn’t bother including the sound of madly cranked-up mic hiss in a test/review (total gain for the MKH 8050, for example, being 85 dB), but in this case it is quite interesting to compare the different capsules. And, as I have cautioned in the past, don’t panic: all the mics are very quiet in normal use!

And here are the spectrum analyzer visualizations of the noise:

The sound files and the spectrum analyzer visualizations show that the two MKH 8018 capsules are quite different in terms of self-noise from the MKH 8050 and MKH 8030. The more limited ultra-sonic capabilities mean that the MKH 8018 is not tuned like its first-order siblings, where steeply rising self-noise towards 20kHz continues to rise to 48kHz. With the MKH 8018, the rise in self-noise in both capsules starts lower and is less steep, and then flattens off after 20kHz. This lower and more gradual rise in self-noise means that the character of the self-noise is quite different in the audible spectrum: self-noise in the MKH 8018 capsules is characterized by more of a high-frequency hiss (say in the 6-12kHz region) very evident to my ageing ears and, obviously, much more so to younger ears. Thinking of younger ears, extreme high-frequency hiss in the MKH 8030 and MKH 8050 will become more discernible to them in the 12-20kHz region as the self-noise in these mics rises to match or exceed that of the MKH 8018 capsules. But, I must reiterate, while interesting to compare and to note for reference, these tests are at extreme gains and so unless recording a watch ticking or other very quiet sound effects, self-noise will not be an issue with any of these mics in most use case. And for an extreme example – relevant to sound design and effects – I slowed down the cathedral bells recording included above to a quarter of its speed, bringing down the pitch accordingly (i.e. by two octaves), and yet no hiss is discernible even in the quiet sections unless gain is cranked up to levels that mean the chimes would destroy your speakers and ears! If interested, do have a play with the downloadable files yourself.

RFI

Looking at radio frequency interference (RFI) on the MKH 8018 is nothing to do with its RF design (which, in the words of the MKH designer Manfred Hibbing in his The MKH Story white paper), means the mic essentially has ‘a transmitter and receiver that are directly wired together’), but is about its resistance to external RFI. As I’ve said in posts on other tests, I am interested in the impact of RFI on mics since, as living in rural Norfolk, much of my life is outside or on the edge of mobile phone reception, where some models of phones transmitting at full power can cause notable interference on mics at up to, say 1m/3ft: not a problem with mics on a stand, but I’ve had this become a real issue with handheld shotgun mics and a phone in my jacket pocket (on those rare occasions when I forget to turn my phone off). And this could be a problem with ENG work too (not least from the phone of an interviewee). So I was glad to find that in testing, as before, with several different phones on the absolute fringe of reception (i.e. working at highest power) the MKH 8018, like its MKH 8000 siblings, showed no sign of RFI even at close distances (100mm): for control I recorded the mic alongside a known problem mic (to check that the intermittent issue was occurring: it was) .

Handling noise

While the MKH 8018 might well see much use mounted on stands (e.g. for line-side recording of sports), it will become a regular fixture in windshields on boom poles or on a pistol grip, whether being used as a mono mic for dialogue or ENG, or in stereo for those times when a bit of ambience is required during production sound recording, or perhaps to get closer to a difficult to access source during field recording. So with that in mind, I put the mic through some boom-pole handling tests, mounting them in Radius Windhsields RAD-2 mounts on a short stereo bar on the end of the boom pole to allow comparison. Gain levels were adjusted for relative sensitivities.

When holding the boom pole statically (extended and horizontally) all four capsules mics showed some handling noise, with the MKH 8050 and MKH 8030 being the most significant, both peaking around 24dB higher than the two MKH 8018 capsules: admittedly the MKH 8050 and MKH 8030 were peaking below 20Hz. This pattern applied across other boom-pole handling tests: rough handling and tapping/thumping the end. To a significant degree – not least given the apparent similarity of the two fig 8 capsule designs – this is doubtless a consequence of the EQ built into the different mics with, as we have seen, the MKH 8018 bass response being very much rolled-off below, say, 50Hz and, especially, below 25Hz. But, equally, there is no denying that the MKH 8018 has handling noise extremely well controlled even without the use of its switchable 70Hz high-pass filter or any such additional, or alternative, filtering in the recorder/mixer or in post.

Wind noise

To get a base line I used a double rig of the MKH 8018 and MKH 8050 + MKH 8030 on a stereo bar and boom pole. Fast boom swings were made to generate wind noise in a controlled fashion. Swinging the bare mics produced overwhelming rumble, as would be expected. The two fig 8s were fairly similar, although the MKH 8030 naturally showed a little more noise at low frequencies (say, below 30Hz). The shotgun mid mic was by far the least susceptible to what was a laminar stream of wind, and the MKH 8050, perhaps surprisingly for some, was by far the most susceptible to wind noise in these conditions. Of course, such use is unrealistic: even with a modest amount of boom movement indoors (or the gentlest air movement around a static mic indoors) at the very least a foam windshield would be used. Matching foams between the mics isn’t that easy, so for the next test I stepped up to bare windshields (i.e. sans fur), using Radius Windshields Mini-ALTOs for both. In tests with the windshields side on and into the wind (again, wide arcs from a boom swing), both capsules in the MKH 8018 performed about 3dB better than their MKH 8050 and MKH 8030 counterparts, and, as expected, lacked the very low-end (sub 30Hz) component: given the testing with a boom, this may well have been as much to do with handling noise as wind. I think another round of spectrum analyzer visualization or even WAV files wouldn’t add anything much to this description, so I will spare you those. Suffice it to say, such limited bare and windshield tests, show that the MKH 8018 is not oddly susceptible to wind (and, goodness, you wouldn’t expect it to be!) and, as you will hear from the samples below, this is further borne out by use in the field.

Out in the field

A shotgun mic, of course, is primarily designed for outdoor use (OK, for large movie sound stages too), given that reflections are the enemy of interference tube designs. So to test the mic in its natural habitat, I put it through its paces recording a fairly wide range of sources outside. Many of these require it to be compared to something else, naturally, or we have no reference, and for most of the tests I have compared the MKH 8018 to an MKH 8050 and MKH 8030 MS pair: the supercardioid MKH 8050 being the most directional MKH 8000 non-shotgun mic (i.e. without an interference tube). Of course a supercardioid mid mic might well not be ideal for MS either in many situations, but you can refer to my recent tests of the MS pairs with the whole range of MKH 8000 SDC mics (i.e. MKH 8020 omni, MKH 8090 wide cardioid, MKH 8040 cardioid and the MKH 8050) if you are unsure of the differences.

First off, I headed to the beach on what I thought was a calm August day, but which turned out to be a brisk on-shore wind. Here are the two recordings facing straight out to sea:

Retreating a bit from the shoreline and the incoming tide to shelter behind the fishermen’s gear, I recorded myself walking on the shingle in a 360 circle around the mics, starting and finishing directly on axis:

Finally, for the seaside recordings, here’s a closer-up effect, recording the scooping up and dropping of shingle right by the mics:

Moving inland, I headed for one of my old test haunts at the North Norfolk Railway. Sadly, both the stationmaster and the signalmen recognized me so I had to take the assumption that I am an uber trainspotter on the chin: to deny it would have seemed as if I doth protest too much and, besides, testing mics is arguably an even more suspect activity! Next thing I will be calling a drink a ‘beverage’: it’s a slippery slope… Anyway, here is a three-clip recording of a steam train pulling into Holt station, then after a momentary gap, the signal box bell ringing and then, after another brief silence, the train pulling out. No editing other than the obvious cutting to produce the three parts to the recording:

Back outside again, I popped over to my friend Rob’s new field (yes. that’s the same Rob who TIG welds the Mega-Blimps!), where he was sycthing or, as he put it, hacking away with a scythe to return the meadow to some order. Doubtless he will crack and get a tractor on it, but in the meantime here’s a pair of recordings of him sharpening the scythe:

And then a bit of scything/hacking at the nettles. I stood rather behind Rob and to the right so as to avoid him slicing through my rather nice and expensive MS cables.

A little bit of music

After all that fresh air I thought I would head inside for an indoor music test, slightly inspired by the well-known use of the Sennheiser MKH 4018-S for the NPR Tiny Desk concerts (although it has been increasingly supplemented by other mics over the years). So I popped down to woodcarver Luke Chapman’s workshop, which I often use: it has a surprisingly good acoustic. Luke obliged yet again (he must be sick of all these tests!) with guitar, working away on a new composition. Here is a video showing the recording with the MKH 8018 compared to an MS pair (again the MKH 8050 and MKH 8030):

Conclusions

This brief introduction to stereo use of the MKH 8018 has covered a bit of ground, from some discussion and tests of the salient aspects of interest from the specs to some tests in use. There are many uses I haven’t included here, partly reflecting my own interests (for example, I’m not in the business of recording sports events, so that’s for someone else to test!) and partly what is practical within a single blog post. One aspect I haven’t addressed is how the MKH 8018 compares to alternatives as a mono shotgun. For some this may well be a determining consideration for buying the mic: in other words, would the MKH 8018 meet their main needs as a mono shotgun mic, whilst providing a stereo option at all times for those occasions where it might prove useful? That is really hard to address, since comparing mono shotguns is not easy, as different sound recordists – especially experienced production sound mixers – will usually need to compare mics directly in use to see whether the nuances of any particular mic means that it suits their use. And, of course, there are many shotgun mics out there. But, that said, I may return to the MKH 8018 to explore the mono shotgun capability in a comparison with its nearest sibling – the MKH 8060: but don’t hold me to it! At the other end of the spectrum, I did think of including results of testing the MKH 8018 as part of a DMS rig here, but haven’t done so for reasons of not wanting to make an overly long post any longer and, also, since the efficacy of any mid mic in a DMS rig is very much apparent from its use in an MS pair. But, again, I may well return to this in a specific post: not least it might be helpful for some to hear the results of using different polar patterns for the rear-facing mid mic (e.g. just what balances a shotgun mic forward facing mid mic best: an MKH 8090 wide cardioid or an MKH 8040 cardioid?).

Anyway, returning to the ground that is covered in this post, drawing conclusions is as much something for the reader as it is for me: my aim was to explore the different in performance between the MKH 8018 in stereo use and an MS pair comprising its most directional non-shotgun sibling – the MKH 8050 supercardioid – and the MKH 8030. Given the better polar pattern and placement (i.e. above, not behind the mid mic capsule) of the fig 8 in the latter, and the more consistent off-axis performance of the supercardioid, its better performance for stereo is entirely expected and is evident in the various recordings. My aim wasn’t to demonstrate this and, as Basil Fawlty would say, get myself on Mastermind with the ‘special subject of the bleedin’ obvious’, but, rather to try and get a sense of the degree of difference. For some users and, indeed, for some uses, it may be vast: for others, and for other uses, the sonic differences may be too subtle and outweighed by other features of the MKH 8018: its usefulness as a mono-shotgun, its simplicity as a single mic vs rigging an MS pair, its ability to be both a shotgun mic and, say, an ambient pair without changing to (let alone buying) a second MS pair, its resilience to handling noise, its inbuilt pad and high-pass filters, and, even, its cost (less than the combined cost of an MKH 8050 supercardioid, or other mid mic, and the MKH 8030). Hopefully this blog post will help some when balancing all these factors. One major obstacle – the significant self-noise of the MKH 418-S – has been removed with Sennheiser’s new stereo mic, and this is hugely welcome. And if you have been humming and hawing about a stereo shotgun mic (including, the slightly noisier and sans RF technology, Sanken CSM 50, Neumann RSM 191, and the Audio Technica BP4027 and BP4029, as well as Sennheiser’s own MKH 418-S), the MKH 8018 is definitely one to get hold of (if you can!) and test for yourself. I’ve been very pleasantly surprised!

Postscript: wind protection for the MKH 8018

There’s nothing difficult in terms of rigging the MKH 8018 for outdoors (the supplied foam, of course, only being suitable for indoor use): it will fit many a windshield from the usual suspects. I note that Cinela have already got a Pianissimo model to fit (and do remember that the Cinela mono models can often be less expensive than you might expect), and a Rycote Modular 4 or a Rode Blimp would work fine. Here, I have tested the mic in a Rycote Cyclone medium, and much of my concern about using the Cyclones for MS rigs is allayed in this instance: the side lobes of the fig 8 capsule do not aim squarely at the thick plastic ring of this windshield, with evident colouration problems, as I have found with MKH 8030-based MS and DMS rigs in the small Cyclone. But the result is far from compact, so for my field tests with the mic I used the new Mini-ALTO 250 from Radius Windshields: they have been expanding their range of Mini-ALTO sizes and this fits perfectly, and I had no problems with wind noise in the admittedly not overly windy conditions of this English summer. And when not lugging two rigs for comparative purposes, I’ve enjoyed the fact that I can fit the MKH 8018 in the Mini-ALTO 250 in its fur, along with a field recorder, headphones, cable, camera etc. all in my little Think Tank Retrospective 7 bag that I like to use for field recording (yes, I know, I know: this is ironic from the creator of the Mega-Blimp!). For the cable I used an excellent low-profile XLR5F to XLR5M stereo cable, made with super-light and flexible Mogami 2739, which really keeps cable-borne noise to a minimum: critical if booming or use the mic on a pistol grip. This was made by Ed at ETK Cables.